WRITTEN BY PEBBLA WALLACE

EDITED BY ADAM LINDER

Like much of America, Los Angeles carries a history that is as beautiful as it is painful—layered with stories of struggle, resilience, and transformation. To truly appreciate where we are today, we have to face the full picture of our past, the good intertwined with the bad. Historian and filmmaker Ken Burns once reflected on this truth, saying, "Being an American means reckoning with a history fraught with violence and injustice. Ignoring that reality in favor of mythology is not only wrong but also dangerous. The dark chapters of American history have just as much to teach us, if not more, than the glorious ones, and often the two are intertwined".

This article is a tribute to Los Angeles’ immigrant and multicultural origins. This is our cities story….

Mural of the Founders of Los Angeles from the Great Wall of Los Angeles/Photo Credit: Meridith Major

America has always been a country of immigrants. For centuries immigrants came as explorers and adventurers to begin settlements, to escape religious persecution, and to flee war and famine. But a very large portion came to work as laborers. These men and women laid the steel that built our railroads, constructed our bridges and raised the buildings that shaped our cities. They cleared barren lands into fields that fed our nation - and even now, not much has changed. Immigrants still come seeking safety and a chance to build a better life, often taking on the toughest, most backbreaking jobs—the kind that most Angelenos today would never dare to do.

LOS POBLADORES – The Original 44

Around 1769, the Spanish Crown appointed Father Junipero Serra the task of establishing missions along the coast of California. The goal of the mission was to convert the native population to Christianity, and solidify Spanish control over the territory. San Diego was the first mission to be established as part of the California Mission system.

Then, around 1781, Governor Felipe de Neve of Las Californias was tasked with founding a new settlement in Southern California. He gathered a group of 44 settlers—known as Los Pobladores—who embarked on a historic journey from what is now modern-day Mexico to the rolling plains of the Southland. Their mission was to establish a new community: El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles. What began as a modest pueblo would, over time, grow and transform into the bustling metropolis we now know as Los Angeles. Today, the legacy of those first settlers lives on at the El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument, nestled in the heart of downtown, just steps away from the lively Olvera Street.

These 44 original settlers consisted of 11 families which totaled 44 people, including wives and children. Traveling alongside these 44 were also four soldiers and 2 priest.

The social background of these first settlers might sound familiar when compared to many of Los Angeles’s immigrants today. They were mostly poor farmers and skilled artisans—ordinary people with extraordinary determination. The artisans, in particular, played a vital role in shaping the young pueblo. Carpenters crafted and maintained the early adobe buildings; blacksmiths forged tools, horseshoes, nails, hinges, and farming equipment; and others contributed their trades to help the small community grow and thrive.

Diversity

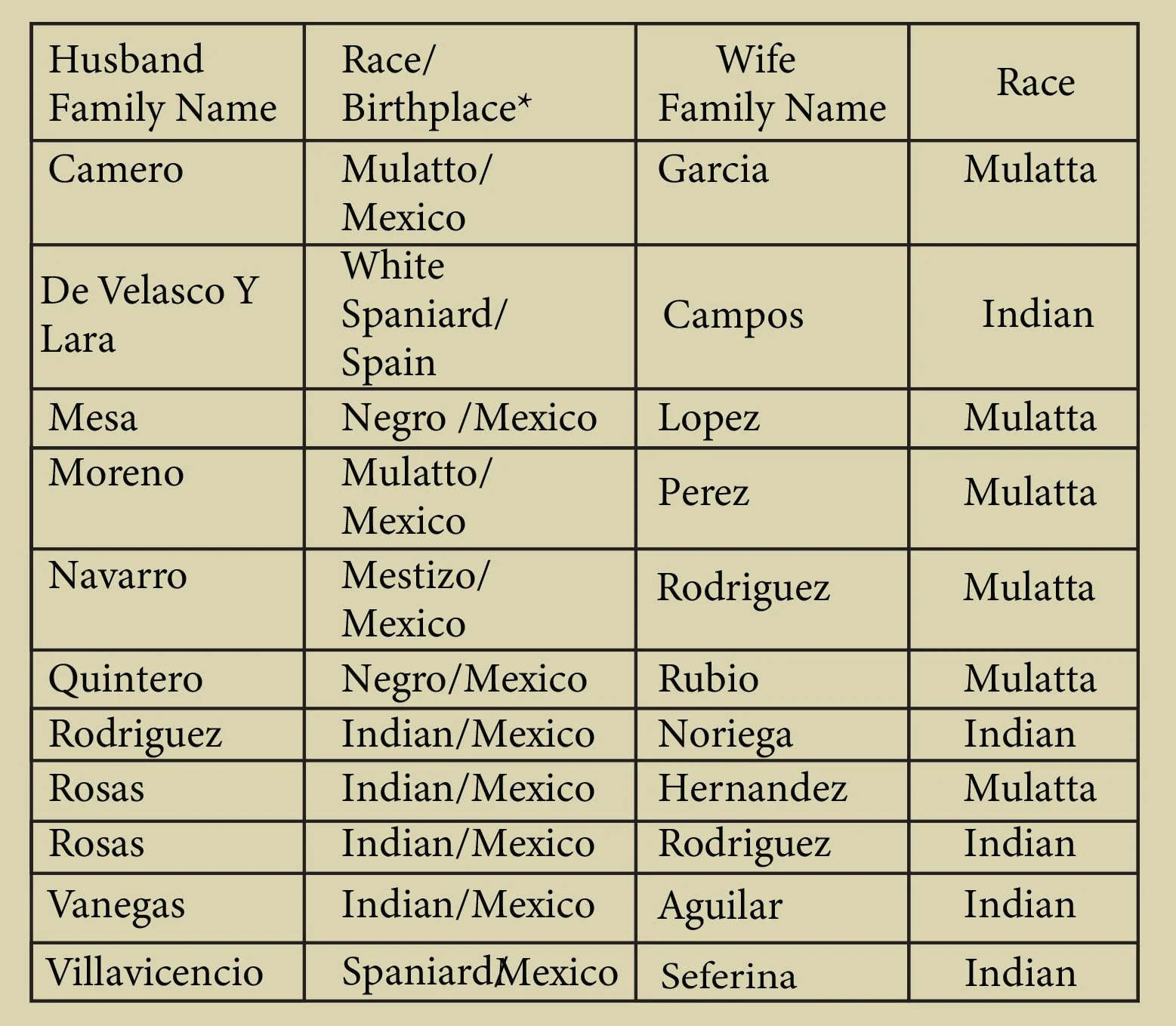

The City of Angels has always been a place of remarkable diversity. From its earliest days, when Indigenous peoples first called this land home, to the arrival of the 44 settlers whose backgrounds reflected a rich blend of Indigenous, Black, and multiracial heritage (see chart below), Los Angeles has been shaped by many cultures. That legacy continues today, as the city remains one of the most diverse in the nation—home to one of the largest immigrant populations in the United States.

Important Note: Thes above racial terms are based on the early Spanish colonial caste classification, and does not reflect today’s understanding of ethnicity.

Our City of Diversity Today.

Many people like to describe Los Angeles as a great “melting pot,” but I’ve personally never quite agreed with that idea. A melting pot suggests that everything blends together until it all looks and tastes the same. That’s not Los Angeles as I perceive it. I think a better description is a “tossed salad.” In a salad, every ingredient keeps its own flavor and texture—each bite offering something different depending on where your fork lands. Isn’t that a better way to think about our city? Los Angeles’s salad is made up of neighborhoods like Little Ethiopia, Koreatown, Little Tokyo, Little Bangladesh, and Chinatown, just to name a few. And beyond those well-known enclaves are countless others—Mexican American, Salvadoran, Central American, Pacific Islander, Jewish, and so many more—each adding their own distinct flavor to the vibrant mix that makes Los Angeles, Los Angeles.

According to the U.S Census Bureau, approximately 57 percent of the residents in Los Angeles County speak a second language other than English in their home. After English, the most common languages spoken in Los Angeles are Spanish (3.7 million), followed by Chinese - Mandarin & Cantonese (390,000), Tagalog (213,000), Armenian (200,000), Korean (170,000), Farsi (109,000), Russian (51,000); Hindi (29,000); Japanese (51,000), Portuguese (16,000), Swahili (4,000). All-in all, there are over 224 different identified languages spoken in Los Angeles County.

California—and especially Los Angeles County—has the largest immigrant population in the United States. The City of Los Angeles itself ranks second only to New York. What this shows is that Los Angeles has always been, and continues to be, a city of immigrants—from its earliest settlers to the people who arrive here today. That enduring spirit of migration and diversity is what makes our city so unique, so dynamic, and such a special tossed salad.

LOS ANGELES – OUR UGLY IMMIGRANT STORY

Mexican Repatriation – Immigrant Raids (1930s)

With recent headlines stirring fear and uncertainty in our immigrant communities, Los Angeles once again finds itself confronting echoes of a painful past—a chapter too long forgotten, known as the Mexican Repatriation.

Note: The Federal Government rebrand the name from deportation to repatriation, to make it seem it was voluntary – which it was not.

In the 1930s, during the depths of the Great Depression, fear and desperation swept across the nation. Jobs were scarce, poverty was widespread, and scapegoats were easy to find. In California, that blame fell on people of Mexican descent—immigrants and U.S.-born citizens alike. Government officials, joined by private businesses, launched an aggressive campaign to remove them from the country. What began as an economic measure quickly turned into a human tragedy.

Central Station Deportation (1932)/Photo Credit: LA Herald Examiner Photo Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

It is estimated that from 1929 to 1939 between 400,000 to 2,000,000 people of Mexican decent were illegally deported from the United States, with the epicenter being California and more specifically Los Angeles County. About 60 percent of those deported were American citizens, many of them children. Families were torn apart; parents were taken from their workplaces, children were pulled from schools. People were coerced into signing documents they couldn’t read, rounded up at bus stations and parks, and loaded onto trains headed south. Entire neighborhoods were left empty—homes, businesses, and farms lost forever. Some families were even defrauded of their property, which was later sold off by local authorities.

Officials claimed these removals would help ease unemployment, but beneath those excuses lay something darker: racial prejudice, fear, and political opportunism. The very people who had helped build Los Angeles—its railroads, its farms, its neighborhoods—were cast out and forgotten.

The loss rippled through the city. Industries that relied on Mexican and Mexican American labor were suddenly crippled by shortages. Those who managed to stay behind faced lower wages, harsher conditions, and discrimination that lingered for decades. Communities that had taken generations to build were dismantled in a matter of months.

La Placita Raid

One of the first immigration raids to take place in the United States was at La Placita Park located in Downtown Los Angeles. La Placita Park was a vibrant cultural center for many immigrants and Mexican Americans to listen to music, talk politics, and socialize. On February 26, 1931, at approximately 3:00 p.m., both federal and local government officials, police officers, and the “Red Squad” (LAPDs anti-communist unit known to violated civil rights with violence to achieve their goals), sealed off the exits to the park so no one could leave. Many of the officials wore military uniforms, but all were wielding some type of weapon. According to the Spanish language newspaper La Opinion, approximately 400 people were originally detained during the raid, several people who tried to flee were beaten by police before being detained. The detainees were lined up and interrogated, asked their name, age, where and when they entered the country, and their employment status.

In the end, the raid lasted 1.5 hours, and the majority of the detainees were able to prove their legal residency. Those who weren’t were roughly handled and dragged off to Central Police Station for further questioning. According to La Opinión, only 17 people were taken to Central Police Station for further interrogation (11 Mexicans, five Chinese, one Japanese). There is no record whether any of those were evey deported.

Plaque recognizing the illegal deportation of Mexican and Mexican Americans (near Olvera Street behind the Plaza Church

Looking back on Mexican Repatriation history.

For many years, this chapter of our history was rarely spoken of. But the silence began to break in 2005 when the California State Legislature passed the Apology Act for the 1930s Mexican Repatriation Program, formally acknowledging the unconstitutional deportation of U.S. citizens and lawful residents. Seven years later, in 2012, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors issued its own apology, admitting the county’s role in these removals. In 2024, a new act of remembrance was signed into law—Senate Bill 537—calling for the creation of a memorial in Los Angeles to honor those whose lives were uprooted and to ensure their stories are never erased again.

The legacy of the Mexican Repatriation still lingers—in the memories passed down through families, in the resilience of communities that rebuilt, and in the ongoing struggle for dignity and justice. The Mexican Repatriation largely ended by the late 1939, though it never had an official “end date” because it was not a formal program with legal oversight. Some Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants who had been deported returned to the U.S. on their own, though many families had been permanently displaced and could not recover lost homes, businesses, or property.

As Los Angeles faces new waves of fear and division, we are reminded of this truth: our strength as a city has never come from exclusion, but from the courage, hope, and humanity of those who call Los Angeles home.